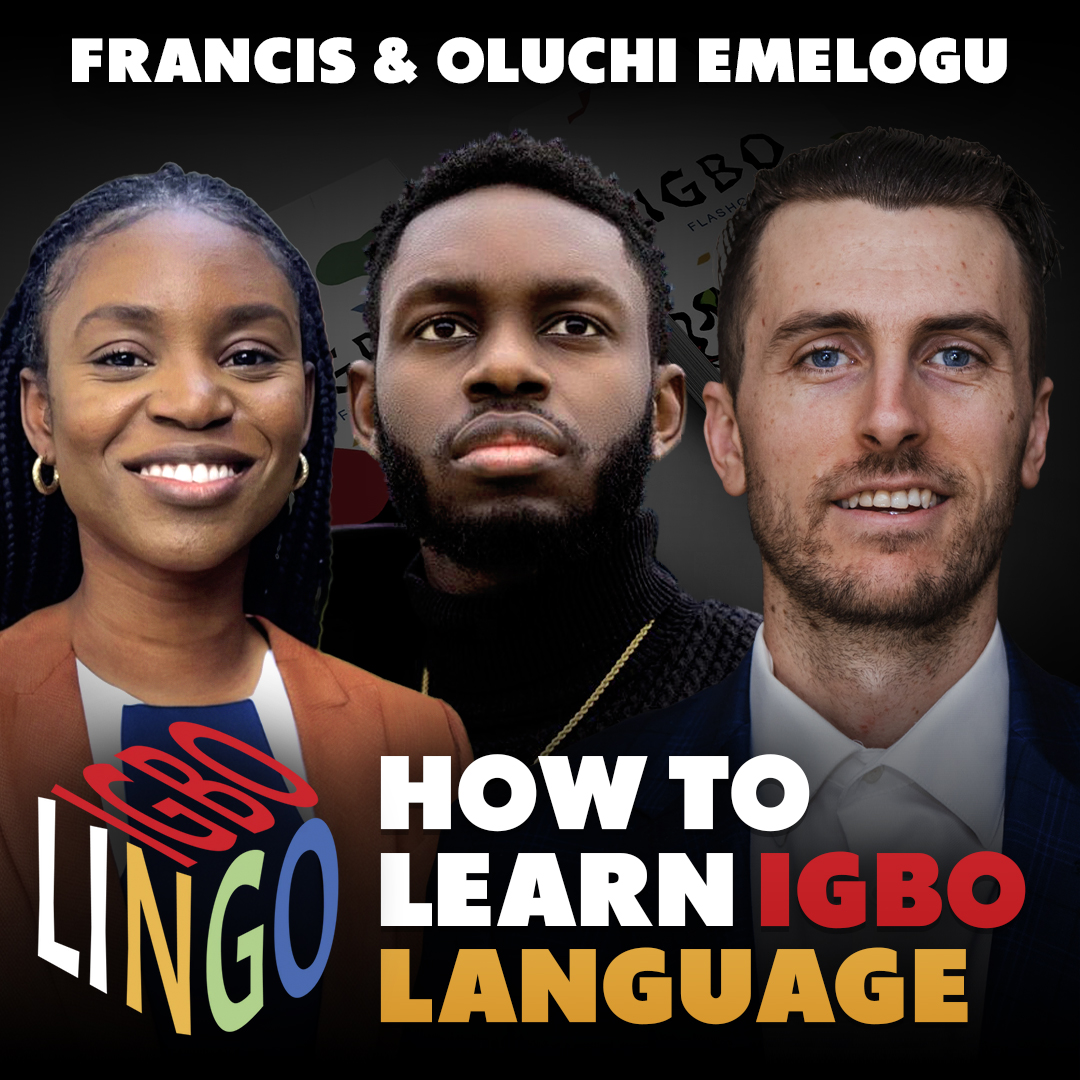

Francis and Oluchi Emelogu are the owners of IGBOLINGO, a company who aims to make it cool and easy to learn the Nigerian language of Igbo through fun and interactive flashcards.

A brother-sister pair from Nigeria, Francis and Oluchi immigrated to the United States at a young age, returned to their native country for boarding school, then ultimately came back to the United States to finish high school.

“In many ways, we grew up in both places,” says Oluchi, who notes that the academic standards in Nigeria were much more rigorous than in America.

“Back home, they used to post our grades in front of everyone, so you knew how everyone was doing in school, and with that came an inherent pressure to perform. Here in the United States, teachers will let you review materials before a test. That made the tests super easy, so school wasn’t challenging, and high school quickly became very boring.”

For Francis, he too excelled in the classroom, but his indoctrination into U.S. culture was not as seamless as it was for Oluchi.

“I was a little bit FOB-ish,” Francis says of his teenage years, citing an acronym (FOB means fresh off the boat) that suggests his transition to the American way of life was not without its hiccups.

“I was still trying to assimilate into the American culture and its social hierarchy,” he adds.

But over time Francis became more comfortable, and his playful nature and sense of humor started to become more apparent.

“I used humor to get attention,” Francis mentions.

Despite needing to acclimate to a new environment, Francis, and of course Oluchi, both thrived in the classroom.

Heavily influenced by parents and a Nigerian culture that expected academic exceptionalism, in college each of them studied to become pharmacists.

In Oluchi’s case, she didn’t immediately become a pharmacist after earning her degree.

“I didn’t want to do the typical CVS or Walgreens route. I wanted to do something that didn’t actually have to do with pharmacy,” she says, which is how she ended up doing a two-year residency program that today has brought her to the VA in San Antonio and enabled her to do more clinical work.

“I’m now more hands-on with the prescription aspect of pharmaceuticals, instead of the filling and processing aspect.”

His sister has found her passion working at the VA in San Antonio, but Francis’ journey through the pharmaceutical world has been more chaotic.

“I didn’t want to be working behind a counter,” says Francis, who initially spent time monitoring clinical trials around the country, a position he relished before the COVID-19 pandemic struck, in turn relegating him to a sedentary workday that quickly sullied his joy for the industry.

“That remote role was unbearable, so I ended up going to work at Tom Thumb as a pharmacist and doing the same thing that I always wanted to avoid, which was being behind a counter.”

Fortunately, moving into a traditional pharmaceutical role didn’t completely decimate Francis’ emotional state.

“That position wasn’t as bad as I initially anticipated because I was working with patients directly and we weren’t doing as much volume as CVS or Walgreens does, and since this was during COVID, I was also giving vaccines and delivering medications,” Francis explains.

Still, Francis did not want to be in that more traditional pharmaceutical role long-term, so in 2021 he began exploring alternative careers within the pharmacy sector, and not long after his search started, he landed a job in pharmaceutical sales.

“I love the sales side of pharmaceuticals, and this is where I want to be,” he says.

For many scientifically gifted individuals, their story would end here, the comforts and predictability of gainful employment enough to sate their career aspirations.

But for the Emelogu siblings, establishing themselves in stable industries was only the beginning of the impact they sought to have on other people.

Oluchi says that she and her brother had always wanted to start a side business.

“The American Dream is to be your own boss,” she reminds us.

“And I always wanted to teach the Igbo language and share it with anyone who wanted to learn it.”

At first, Oluchi experimented with running an online course for the Igbo language, but she quickly discovered that a lot of people weren’t looking for an intensive course that would expedite their path to fluency.

Rather, many of the people interested in learning the Igbo language were just as curious about the culture as they were the subtleties of Igbo grammar.

At that point, Oluchi consulted with Francis, and collectively they agreed that the most effective way to appeal to their target demographic was through flashcards that offered visuals for each word, as well as proper pronunciation.

“With the flashcards, I could create illustrations that would be able to explain what each word meant,” says Francis, a skilled artist who previously drew comics for the school newspaper and competed in contests during his postgraduate studies.

“Another cool thing about the flashcards is that they would appeal to both adults and to children.”

Armed with a unique concept that differed from all the language programs readily available online, Francis and Oluchi then began the process of bringing the flashcards to market.

For context, the duo did not create flashcards for every word in the Igbo language.

In fact, they didn’t manufacture a flashcard for most words in the language (there are 52 words in the first set of Igbo flashcards).

Oluchi says this decision was intentional.

“There are so many words in the Igbo language, to the point that it would be impossible to create a set of flashcards for all of them, but this is why I love our business idea,” she says.

“Instead of trying to fit thousands of words into a set of flashcards, we’ve decided that we are going to come out with different editions of the flashcards.”

Each edition will feature commonly used terminology that covers family, numbers, food, etc.

Throughout these editions, the emphasis again will not be on building native-speaker level fluency, but keying in on crucial pillars like vocabulary and pronunciation.

“We can’t put the entire language on the flashcards. That wouldn’t be feasible because there are simply too many words,” Francis reiterates.

“But we want to capture and highlight the most important parts of our culture.”

At present, there are no other flashcards that teach the Igbo language quite like those that Francis and Oluchi have assembled.

Not even Duolingo offers users the chance to learn this idiosyncratic language.

Moreover, Nigeria was colonized by Britain in 1884, and consequently, many pronunciations of words in the Igbo language make it difficult for American English speakers to properly grasp the original Igbo dialect.

If this discrepancy seems negligible or unimportant, consider that for people learning English as a second language, the word “water” is pronounced differently in the United States versus in England.

Of course, to native English speakers, understanding the difference in pronunciation is easy, but to someone who isn’t adept at the English language, this disparity becomes utterly confusing.

Which is why the Igbo flashcards that Francis and Oluchi have created are so paramount, especially for Americans learning the Igbo language.

“No one has explored the nuances of the American English translation of the Igbo language like we have,” Oluchi says.

“If Duolingo had Igbo, that would be great. There then wouldn’t be as much of a need for our flashcards, but it doesn’t, so we are here to fill in that gap.”

Undeniably, the functionality and tangibility of these flashcards are allowing Francis and Oluchi to capitalize on the sizable void in the Igbo language learning market.

But more impressively, the pair’s idea is also being extrapolated to include other languages.

Already IGBOLINGO has produced and manufactured flashcards in Yoruba, a language that has upwards of 50 million speakers who are located primarily in southwestern and central Nigeria.

Oluchi says this expansion into other languages wasn’t planned, but as happens so often in business, the market spoke.

Francis and Oluchi were simply wise enough to listen.

“When we came out with the Igbo flashcards, then Yoruba speakers wanted flashcards in their language,” says Oluchi, in mentioning that she also has a friend from Ghana who is now advocating for IGBOLINGO to produce flashcards in Twi, Ghana’s most widely spoken language.

Not that Oluchi or Francis are particularly bothered by the increase in demand.

“Any African language that we see a demand for, we will create flashcards for them as long as we can find collaborators and people to help us put them together,” Oluchi says.

Adds Francis:

“Our mission is to preserve culture and language.”

“We have the process down for how to create, manufacture, market, and ship the flashcards, but much like is happening now with Yoruba, we need champions of other languages to drive this product forward.” QS

**

Today’s post is sponsored by:

Graham Riley and his team at Maverrik North America help entrepreneurs and business owners increase their reach on LinkedIn, which in turn generates more revenue.

If you’re looking to expand your presence on LinkedIn, then get in touch with Graham today by clicking the link above, or by scanning the QR code in the accompanying image!

jisie nu Ike na mbo unu n’agba ikuzi asusu Igbo na obodo Amerika. Onye nwe anyi gbaa unu ume oo!

LikeLike